The Chicken Hidden in the Canoe

ʻO le Tala o le Moa i le Vaʻa

Samoan children’s games are so fun, common games include pōpō manoʻo (a hand-slapping game), mūfoaʻi (Samoan checkers, where the object is to get rid of your pieces first), and sapo (a stone-tossing game), ʻeli le palai (“dig the yam,” a sort of cross between hide-and-seek and capture the flag), and ʻe te lulu ʻe te moa (“you owl, you chicken,” a far more raucous, unruly cousin of “duck, duck, goose”).

This tala (tale) is the backstory to the ʻe te lulu ʻe te moa game, courtesy of Vaisala village on the island of Savaiʻi.

For the old Samoans, many “chores” were communal activities; from paddling a canoe, working plantations, and building a house, to weaving mats. Workgroups had a structured workflow and designated leadership roles that had ceremonial nicknames.

Often this mirrored the at-large village governance -- a chiefʻs son could lead boys in harvesting bananas, or a chiefʻs wife might preside over a village weaving session -- but tasks could also be designated on a rotating basis, as local tradition dictated.

For example, in weaving mats, the leader of the weaving group sat in the place of honor inside the weaving house and was called Matua-uʻu (“Motherly Cutting-shell”), even if she was a young woman.

This tale involves the communal designing of tapa cloth (siapo), and the leader of siapo-making groups is nicknamed the Sina.

On the northwest coast of Savaiʻi island, at the foot of the Vaisigano Mountains, lie the picturesque villages of Papa, Sātaua, Fagasā, Vaisala, and ʻAuala. The women artisans of these villages prided themselves on the beautiful siapo they created in a style that was unique throughout the entire island chain.

Everywhere else in Sāmoa, siapo was made by either freehand painting (mamanu), smoking (faʻaasu), dying (fui), or stencil-rubbing (ʻelei) on handmade printing boards.

But, the siapo from this region was distinct because of the Papaloa, a natural rock formation east of Vaisala Bay. It was there that nature had created an extraordinary stencil board when an ancient lava flow had hardened into whorls and ripples that gave the siapo artisans of the neighboring villages an endless array of intricate patterns to rub onto their cloths in countless combinations.

The ladies always enjoyed their monthly excursion to Papaloa. They left the children in the care of the village men and enjoyed an entire day of painting siapo beside the sea. The leader of these siapo-making groups was designated as the “Sina,” and it was the Sinaʻs job to delegate tasks to ensure the successful completion of each batch of siapo.

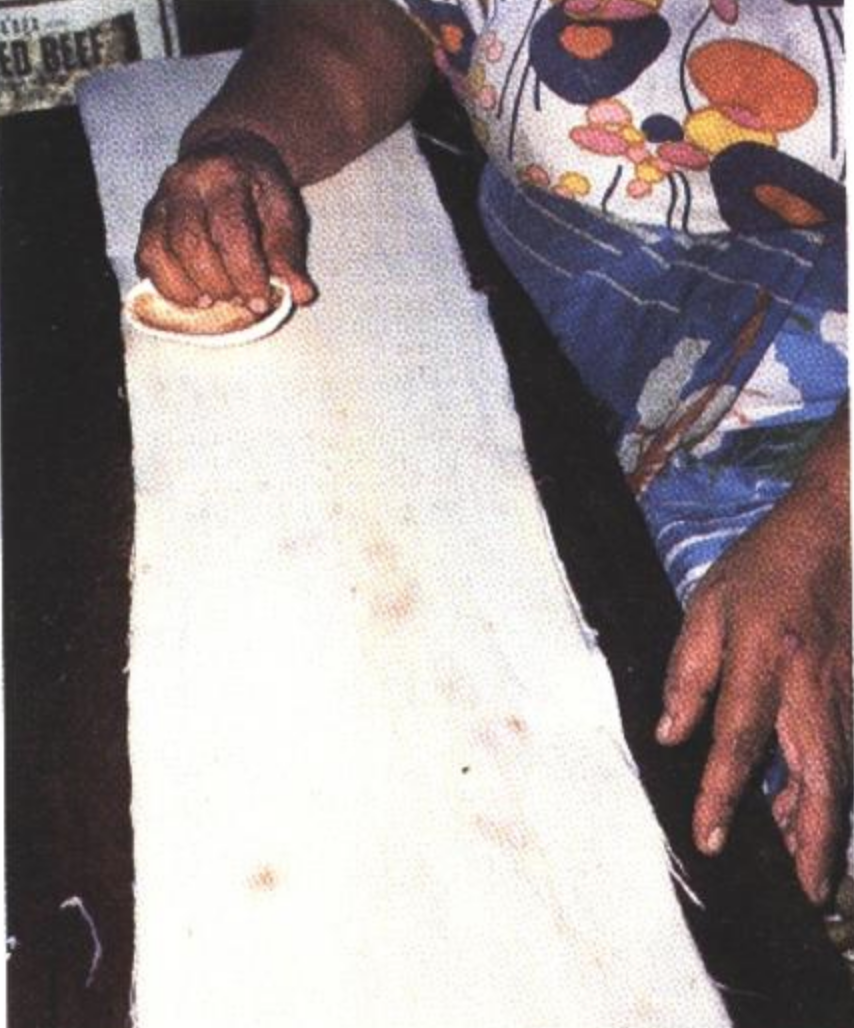

The Sina diligently oversaw the harvesting and replanting of the uʻa saplings that provided the bark to make the siapo with. She taught and encouraged proper technique as she and her peers painstakingly peeled the bark and separated the fibrous inner layer from the tough outer bark. They then cleaned, trimmed, scraped, and smoothed the bark strips (applying different levels of pressure and using seashells with different textures and grooves to achieve the desired result). The cleaned, bundled strips were then pounded out into smaller sheets, which were layered and pounded to form large sheets of white siapo, ready to be decorated.

Throughout this labor-intensive process, one of the favorite songs sung by the artisans told the legend of Fulu-fulu-a-le-lā, a Fijian king (supposedly a cannibal) who sailed to Sāmoa in search of a husband for his daughter, Tutuga. The king was impressed that Sāmoa was indeed a land of clever men with warrior prowess who could strengthen his family tree, but he was appalled that Samoan houses had no walls and that Samoans slept without bedsheets or blankets. He could never leave his daughter to live in such a country with no privacy or comfort!

Fulufulualelā arranged the marriage of his daughter on one condition: “I leave tomorrow for Fiji,” he said, “and I will provide you with what you lack. You will cover my daughter with siapo, or I will return and take her back.”

A month later, Fulufulualelā returned with his daughter Tutuga, draped in layers of fine Fijian siapo. As part of her tōga dowry, she presented the Samoans with the first uʻa seedling so that they could make their own siapo cloth.

Because of this generous gift, “tutuga” (the name of the Fijian princess) is still the honorific word for the uʻa plant today.

Before the sun rose, Sina directed the village women to load the canoes with bundles of their unpainted cloth, freshly squeezed plant dyes, water jugs, etc. With a loud blast of the conch shell trumpet, the women dug their paddles into the sea and headed off for Papaloa with lively cheers.

A long dayʻs work was always rewarded with a hearty feast, and Sina had personally loaded the last canoe in the convoy with a basket of taro, a cluster of green bananas, a mound of yams, a cage full of chickens, and a fat piglet.

After an hour of paddling, they arrived at Papaloa. Sina made sure everyone knew their assignment and had the tools they needed to complete their task. Some women got to work building a shady pavilion, others hiked to fetch spring water, while the old ladies were escorted to choose their favorite stencil rocks first.

In the midst of the hustle and bustle, Sina realized one canoe had not yet arrived -- the one carrying the food. Maybe one of their paddlers got a cramp, or the outrigger came loose… whatever it was, Sina was sure they would come sailing up the coast soon.

In order for the feast to be ready in the evening, the “food team” needed to build and light the umu, prep the vegetables, butcher the livestock, dive for seafood, and allow enough time for it all to cook…. and the day was passing by quickly.

What Sina did not know was that the women she had selected for cooking duty were angry with their assignment. They wanted to paint siapo, not peel vegetables and gut a pig for other people to eat. So, the disgruntled women had paddled into a cove, prepared an umu for themselves, and ate until they were too stuffed to move.

One scrawny chicken was all that was left over, and the women decided to hide it in a basket and keep it for themselves to cook back home. It was late afternoon by the time the food canoe was sighted.

The siapo work was done and the tired, hungry women let out a relieved cheer. But their excitement was short-lived as they noticed the canoe was riding high in the water and the paddlers seemed to be pulling the canoe with little effort at all.

This could only mean that the canoe was empty!

The greedy ladies had rehearsed a devious story, which they told as they landed on the beach.

“Sina! Sina! Oh, how happy we are to see you! We lost absolutely everything when a wave flipped over the canoe!” Wise Sina wanted to teach them a lesson by catching them in their lie.

She told them all to scoot to their left, “faʻapeapea ā!” and they did so, “ī ai ā!”

She could see that there was not any water in the bottom of the hull.

“How strange,” Sina said, “The seats are dry and your hair has not dripped. Not what I would expect from a boat that had just flipped.”

She told them all to scoot to the right, “faʻapeapea ā!” and they did so, “ī ai ō!”

The shifting of the boat jostled the hidden food basket and the chicken clucked in surprise. “What kind of fool do you take me to be?” Sina said. “It’s obvious not everything was lost in the sea.”

Caught in their lie, the embarrassed women confessed to their wrongdoing and asked Sina for forgiveness.

Because their arms were fresh and rested (from paddling an empty canoe), the cooking crew paid their penance by tying all the canoes behind theirs and towing everyone home, where they prepared everyone a very late dinner.

From that day on, it became customary for the cooking crew to wake up in the middle of the night to cook the umu and provision all the canoes with cooked food before the travelers left in the morning.

Today, the words usupō (“singing in darkness”) and umu-tuʻu-vaʻa (“sending-off-the-canoe umu”) still apply to preparing a meal in the early morning hours for travelers or workers to take with them.

Sina! (ʻioe!) Sina! (ʻioe!)

Na ou sau nei fai mai e Sina

Avatu se moa, fai ʻai mo le ʻeleiga

ʻO ā mea foʻi, le mātou vaʻa

Na sau mai Papa, ua lele moa

(Ia faʻapeapea ā!) Ī ai ā! (Ia faʻapeapea ā!) Ī ai ō!

Sina! (Yes!) Sina! (Yes!)

I came here because you (Sina) instructed us,

To bring chickens and cook food for the siapo workers,

Well..what happened was… our canoe.

On the way from Papa village... the chickens flew away,

(Move out of the way!) Uh oh! (Move the other way!) Oh no!

MORAL OF THE STORY

Morals of the story according to grandma include: if you have problems with someone, take it up with that person directly and don’t involve others unnecessarily; if you donʻt like something, speak up early instead of letting things escalate; be honest.

HOW TO PLAY ʻE TE LULU ʻE TE MOA

ʻE te lulu ʻe te moa is a variation on the game of tag, where all the children (except the tagger, who is called the "lulu") line up single-file and form a "canoe" by placing their hands on the hips or shoulders of the kid in front of them.

The last kid in the "canoe" line is the "moa" (chicken) and all the kids in front are the "auvaʻa" (canoe paddlers/crew).

The object of the game is for the "lulu" (owl) to catch/tag the "moa" (chicken), which is made hilariously more complex by the ʻauvaʻa who try to protect the "moa" by distracting or blocking the "lulu," or coiling the canoe-line around the "moa" (all while staying connected by the waist/shoulders the whole time).

When the lulu succeeds in tagging the moa, everyone rotates back one position in the "canoe" and a new round starts with the kids singing a call-and-response chant derived from the story, with the "lulu" acting the part of Sina, and the ʻauvaʻa playing the canoe crew that tried to hide the chicken.

When the lulu sings, "ia faʻapeapea ā," all of the other children lift their right arms and legs and yell, "ī ai ā," then lift their left arms and legs and shout, "ī ai ō" (alluding to Sinaʻs inspection of the canoe hull in the story).

When Sina/lulu spots the moa at the back of the canoe, then the chase begins with boisterous laughter.

CHARACTERS

Fulu-fulu-a-le-lā: Fijian king

Tutuga: daughter of Fulu-fulu-a-le-lā

Sina: Nickname for the leader of siapo-making groups

PLACES

ʻAuala, Fagasā, Papa, Papaloa: Villages on the island of Savai’i

Vaisigano Mountains

VOCABULARY

ʻElei: method of making siapo by stencil-rubbing on handmade printing boards

ʻEli le palai: “dig the yam” game

ʻE te lulu ʻe te moa: “you owl, you chicken” game, tag

Faʻaasu: method of making siapo by smoking

Fui: method of dying siapo by immersion

Lulu: owl

Mamanu: method of making siapo by freehand painting

Matua-uʻu: (“Motherly Cutting-shell”) leader of a weaving group

Moa: chicken

Mūfoaʻi: samoan checkers

Pōpō manoʻo: hand-slapping game

Sapo: stone-tossing game

Siapo: tapa cloth

Sina: the leader of siapo-making groups

Tōga: cloth dowry

Tutuga: honorary name of uʻa

Uʻa: paper mulberry, bark used for making siapo

Umu: earthen oven

Umu-tuʻu-vaʻa: “sending-off-the-canoe” umu, meal prepared in the morning or before travel

Usupō: “singing in darkness”

MEDIA

Article: Don’t Leave Savai’i Without A ‘Siapo’

REFERENCES

Thomas, Allan. " Traditional Games: Recording Experiences in Pacific and European Cultures." The Journal of New Zealand Studies [Online], 3.3 (1993): n. pag. Web. 20 Jul. 2020 https://core.ac.uk/reader/229703538

Whistler, W. Arthur. “Annotated List of Samoan Plant Names.” Economic Botany, vol. 38, no. 4, 1984, pp. 464–489. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4254688. Accessed 19 June 2020.

More on Games:

Thomas, Allan. " Traditional Games: Recording Experiences in Pacific and European Cultures." The Journal of New Zealand Studies [Online], 3.3 (1993): n. pag. Web. 23 Jul. 2020 https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/jnzs/article/view/297/221

GENERAL DISCLAIMER & COMMENT RULES

We recognize that as a result of Sāmoa’s rich oral history, it is likely that multiple versions of these stories exist. As such, we do not claim that the stories featured in this site are authoritative. As a collective we encourage both new stories and variations of stories to be shared so that we might be able to have a deeper and broader understanding. Comments are encouraged and welcomed, however we require that comments are productive and given with respect and decorum. Disagreements should be supported by providing constructive feedback and arguments or the most preferred method, submitting your variation of the story.

Credit will be given to contributors with their permission. For more information on contributing a story click here.

Tell us what you’re favorite vavau (traditional) Sāmoan game is in the comments!