The War between the Flying Animals and Animals of the Sea

O le Taua o Manu Felelei ma Iʻa o le Moana

Tifi-tifi-pule (the latticed butterflyfish) was the chief of the reef. He spent his days floating among the corals and showing off his shiny yellow scales.

Ti’otala (the flat-billed kingfisher) was the chief of the coastline. He spent his days flying between the trees and showing off his bright blue feathers.

One day the butterflyfish saw Ti’otala flying overhead and yelled out from the water,

“Hey little bird, you may be blue like the sea, but you’ll never rule the whole ocean like me.”

The kingfisher flew down to the water’s surface and yelled back at Tifi-tifi,

“Hey little fish, you may be king of the sea, but youʻll never be king of the skies like me.”

As their arguing got louder and louder, the reef fishes began gathering around Tifi-tifi and the birds began flocking around Ti’otala.

Each side claimed to be the best, the strongest, the fastest, the prettiest, and soon the entire coastline was a frenzy of snapping beaks, splashing fins, and flapping wings.

The two arrogant chiefs decided there was only one way to settle their argument, and that night war was declared between the animals that swim in the sea and the animals that fly through the air.

Ti’otala perched on a high branch and called out to his army of birds, bats, and insects:

“This is our chance, just follow me! We will rule the skies AND the sea!”

Tifi-tifi sat on his coral throne and addressed his army of turtles, dolphins, and eels:

“Some of you will live, and some will die, but we will win the power to FLY!”

The war began at first light. When the tide was high, the sea creatures rode the waves right onto the land, a surprise attack against the sleeping shorebirds!

Then when the low tide retreated, the shorebirds flew out to the exposed reef and fought in the shallow water.

One brave bird named Sa’ula-lele decided to take the fight to deeper water. He flew high into the sky and then dove straight down into the water, impaling fishes with his long, sharp beak.

Each time he dove into the water, he became a little bit more like a fish and a little bit less like a bird.

Sa’ulalele (Sailfish)

The sailfish is named for its sail-like dorsal fin and is widely considered the fastest fish in the ocean, clocking in at speeds of 70 mph. This species is a highly sought-after game fish that is easily recognized by its long upper jaw, which it uses as a spear to strike and stun larger prey, such as large bony fish and cephalopods.

By noon, he had grown gills and after diving all afternoon, his feathers had become scales! Just before sunset, his wings turned into fins and he became the sailfish, never again to return to the skies.

If you look closely at a sa’ula-lele today you’ll still see him chasing fish underwater and attacking them with his long, pointy beak.

Se’emu, the tiny dragonfly, showed her bravery by challenging Tifi-tifiʻs best warriors: Tafolā (the enormous humpback whale) and Mumua (the swift, genius dolphin).

The whale lifted its immense tail out of the water and tried to slap the dragonfly, but Se’emu flew swiftly out of the way.

The dolphin leaped high out of the water and tried to catch the dragonfly in its mouth, but Se’emu nimbly flew out of the way.

When the exhausted Tafolā and Mumua surfaced to gulp a breath of air, the dragonfly flew as fast as she could and stung them on top of their heads, leaving a big hole.

If you look closely at a tafolā or mumua today, you’ll notice they still jump out of the water, slapping their tails and fins, as if trying in vain to swat Seʻemu (and whales and dolphins still have a blowhole on top of their heads).

The animals fought all day and all night and they were exhausted.

The Matu’u (heron) realized that no matter how hard he tried, he could not breathe underwater like the Feʻe (octopus). The Asi (yellowfin tuna) accepted that no matter how high she jumped, she could not soar through the air like the ʻAtafa (great frigatebird).

As a last ditch effort, one frustrated shark decided to charge ahead and fight on dry land, ramming its head straight into a sandbar. The impact flattened the shark’s face and squeezed its eyes (mata) out of its ears (taliga).

All the other sharks laughed and called him Mata-ʻi-taliga ("eyes in the place of ears"), the Samoan name for the hammerhead shark.

Mata’italiga (Scalloped Hammerhead Shark)

If you look closely at a mata’italiga today, you’ll notice it still has a flat face with eyes that protrude from the sides of its strangely-shaped head.

Photo: Larry Basch

Finally, a truce was called at midnight, under the bright light of the full moon, and the war between the fliers and the swimmers ended. Chief Ti’otala gave up his campaign to rule the sea, and chief Tifi-tifi-pule promised to never try to invade the island.

As a gesture of friendship, the Manumea (tooth-billed pigeon) gave its strong beak to the Fuga (parrotfish), and the Tulī (plover) gifted its skinny beak to the Gutumanu (forcepsfish).

If you look closely at the fuga and gutumanu today, you’ll see that these fish still have mouths that look like bird beaks.

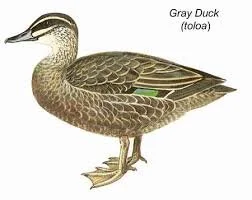

In honor of the peace treaty, the Maoa’e (large reef eel) gave its skin to the Toloa (duck). If you look closely at the toloa’s webbed feet today, you’ll see that it still looks and feels like an eel’s skin.

Every animal had fought bravely to defend their leaders’ honor, except for one selfish, lazy fish named Mālolo (the flying fish).

It was discovered that whenever the swimmers had been ahead, Mālolo swam among their ranks and cheered for the fish. But, whenever the flying animals had the advantage, he had stretched out his fins and flapped them like wings, pretending to be a bird.

Because of his disloyalty, Mālolo’s fins remained stretched out forever so that all the animals would know that he had been a traitor. If you look closely at the mālolo today, you’ll see that its fins still look like wings and that he can still jump out of the water and skim over the waves like a bird.

MORAL OF THE STORY

In old Sāmoa, there were many legends of wars between natural elements – fish against birds, rocks against trees, wind against soil, etc. While these stories may seem like pure make-believe, many of them may have actually been poetic ways to describe real conflicts between villages, districts, or families.

The moral of the Taua o Manu Felelei ma Iʻa o le Moana is that every person, like every animal in the story, has a unique place in this world and a meaningful role in society. Sometimes identity can change (like a shorebird becoming a sailfish), often we gain through sharing (like the toothbill pigeon giving its beak to the parrotfish), sometimes we take on big challenges (like a dragonfly fighting a whale), and we can always learn from the example of others (find a better way to get ashore than ramming your face into the beach!).

Another major theme in the story is that of loyalty and honesty. Those animals that answered the call of their chief are seen as exemplary heroes, while the flying fish wound up living a hard life of constant distress -- always in danger of being eaten by both fish and birds -- because of his disloyalty and dishonesty.

MEDIA

Save The Manumea Campaign

CHARACTERS

Asi: Yellowfin Tuna

ʻAtafa: Great Frigatebird

Feʻe: Octopus

Fuga: Parrotfish

Gutumanu: Forcepsfish

Mālolo: Flying Fish

Maoa’e: Large Reef Eel

Manumea: Tooth-Billed Pigeon

Mata’italiga: Scalloped Hamerhead

Matu’u: Reef Heron

Mumua: Dolphin

Saʻulalele: Sailfish

Se’emu: Dragonfly

Tafolā : Humpback Whale

Tifitifi-Pule: Latticed Butterflyfish

Ti’otala: White-collared Kingfisher

Toloa: Duck

Tulī: Plover

GENERAL DISCLAIMER & COMMENT RULES

We recognize that as a result of Sāmoa’s rich oral history, it is likely that multiple versions of these stories exist. As such, we do not claim that the stories featured in this site are authoritative. As a collective we encourage both new stories and variations of stories to be shared so that we might be able to have a deeper and broader understanding. Comments are encouraged and welcomed, however we require that comments are productive and given with respect and decorum. Disagreements should be supported by providing constructive feedback and arguments or the most preferred method, submitting your variation of the story. Credit will be given to contributors with their permission. For more information on contributing a story click here.

Tell us what your favorite animal is in the comments below!